Why you don't need that new and cool device everyone is talking about?

Buying a new device is not always a good option. This is because devices emit carbon long before we start using them. Find out why this happens and how can we help, in this article.

Hi there, it's been a while you've seen me in your inbox, or on the website.

To be honest, I didn't feel like writing. To be able to answer why, I would need to know the reason, so we will not do that here.

However, I do want to change that! And improve on the matters at my blog. My plan was to publish an article every two weeks, but plans are there to be modified, or scraped if we're not up for them, right? Well, the plan still remains, and even though I've missed a couple of the two-week articles (four, to be exact), I'll try to stick to it. How? I don't know. But you'll find out.

Now, to address the tittle of the article. The short answer is rather obvious - it is not good for our environment. We'll go through the longer answer in the paragraphs below.

What is embodied carbon?

So, let's start at the beginning - why is buying new device(s) not good for our Planet? The reason is embodied or embedded carbon. This is the amount of CO2eq that is emitted during the production of the device(s) that we use. Being it a smartphone, a laptop, smartwatch, headphones, servers, TVs, and so on, and so forth. Each of these devices contains embedded carbon.

This is because the production process is quite complex and requires quite a lot of materials. Each of that material is extracted from different parts of the world. The process of extraction is a problem on its own, with a lot of carbon emissions. Additionally, the amount of electricity and water spent in these processes is quite extensive. And the electricity used in production is not always clean, adding to the amount of carbon emissions.

How to measure it?

This is not as easy as it sounds. We have a plethora of devices, and each group of those devices have different production processes, amount of material used, and lifespan of the device.

We can divide carbon emissions from devices in two categories. The emissions happen during:

- manufacturing and

- using the devices.

Here, we're focusing on the emissions during the manufacturing process.

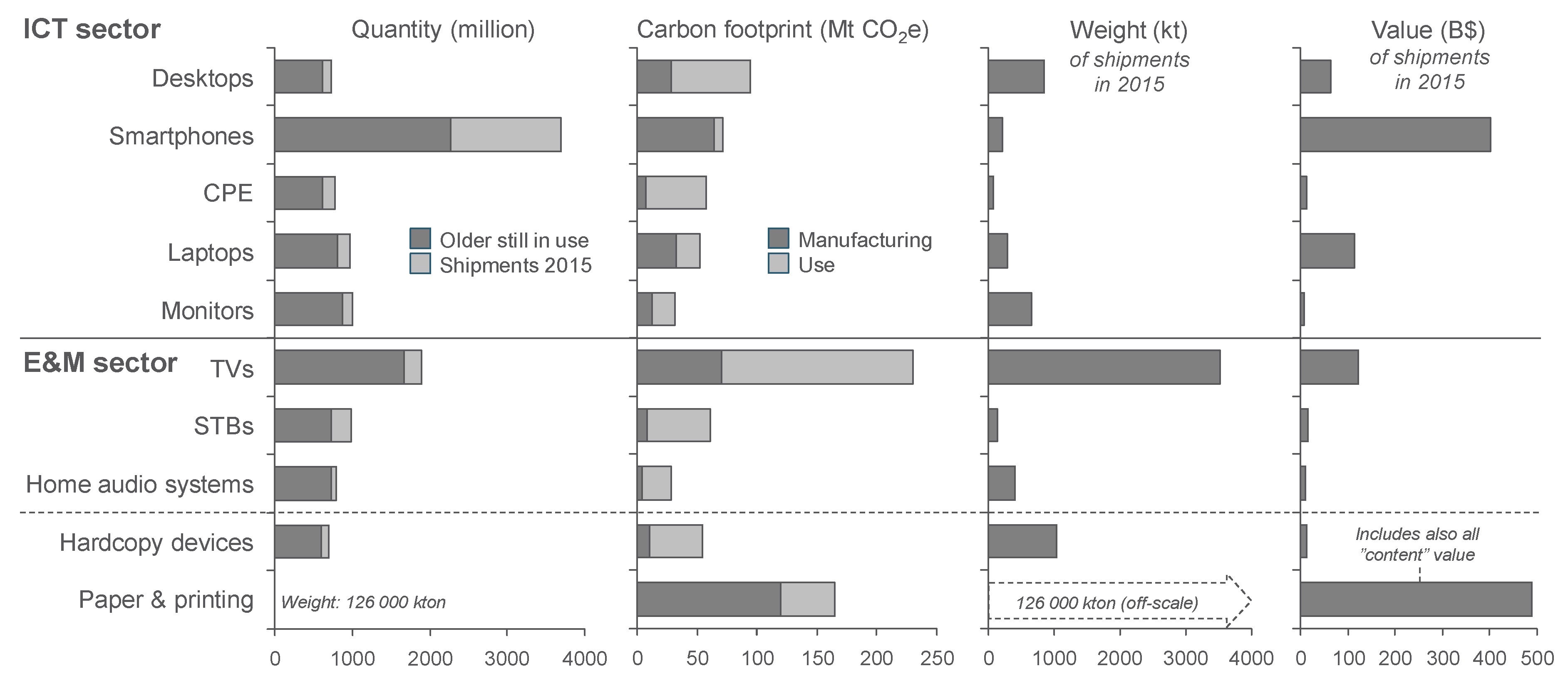

The table below shows the Information and Communication (ICT) sector and Entertainment and Media (E&M) sector quantities, carbon footprint during manufacturing and use, weight of shipments, and overall value of shipments.

A quick note on the section below the E&M sector. Hardcopy devices and Paper & Printing are considered a sub-sector of E&M. It includes traditional paper media as well as office and home printers and similar equipment and their energy consumption. For example, printers, copiers, faxes, and combo-devices. [1]

Let's focus on the Carbon footprint part. As you can see from the table above, quite a lot of carbon emissions are happening during the manufacturing. Especially the manufacturing of smartphones and laptops.

In other words - a lot of carbon is emitted to produce and ship that device to you instead of you actually using it.

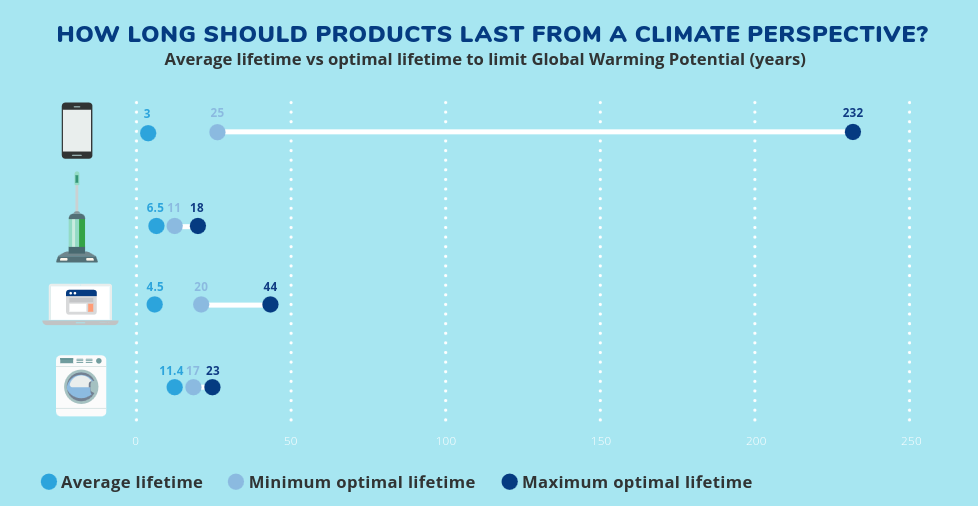

Let me quickly post a reminder table below, referenced in my article on finite computing resources.

You can see here that the minimum optimal lifetime of a smartphone should be ~25 years, and for a laptop ~20 years. [2]

Is that even possible? Let's find out.

How can we help?

It can be quite overwhelming when you first hear, see, or read these numbers. You can even end up feeling depressed. At first.

Next stop is - what action can we take to improve this?

There are a couple of ways we can do this. Some of the steps we can take alone, but for others, we would need some help.

Increasing the lifespan

The first logical step is to keep using the devices you have, for as long as that is possible. For example, I have been using my previous phone (Pixel version 2) for more than 6 years. I bought one of the two laptops I'm using, 8 years ago. It is a Lenovo ThinkPad T450 (not an IBM Thinkpad, unfortunately) which I bought used. And I am not even sure how long it was used before I bought it. Maybe I can check that.

The second laptop I'm using more actively was also used (by me) before I bought it from my company when the warranty expired. After 4 years.

So, it's possible. Not as easy as it should, but it is.

If you have been using your laptop or smartphone for quite some time, and really want a change, make sure to check more sustainable options like:

The above two companies give the right to repair back to you, which I think is most important!

Building more lean software

This is more centred towards the software engineers out there. The problem of the plethora of software available today is that it is bloated and over-complicated.

Why does the Android system with no apps takes up almost 6GB? Why the Docker images take more than 350MB? Because of the complexity and dependency bloat we've introduced in our applications.

This increase in complexity and bloat requires devices to perform better. E.g. have more storage or CPU cores. Our existing devices cannot handle that as well. And we end up in a vicious cycle of consumerism.

Well, bigger doesn’t imply better. Bigger means someone has lost control. Bigger means we don’t know what’s going on. Bigger means complexity tax, performance tax, reliability tax. [3]

The incomprehensible should cause suspicion rather than admiration.[4]

We cannot do this alone. We need to make decision makers, stakeholders, aware that over-complicating software, and bloating it with dependencies, doesn't have just security concerns. It also has environmental concerns.

Regulate for right to repair

The right to repair is a user's right to repair their device(s) and in that way increase the lifespan of it. This also means that manufacturers need to:

- repair products for reasonable price and within a reasonable time frame after the guarantee period has expired;

- guarantee access to the spare parts, tools, and repair information for the reasonable amount of time;

- focus on repair first;

- assist consumers in repair process.

As far as I know, this rule is adopted in the EU.[5] I'm not sure about the rest of the world, maybe some states in the US.

Summary

Finally, we've reached the end of the article. In it, we (hopefully) learned the following:

- Embedded carbon is the carbon emitted during the manufacturing of the device.

- Measuring the embedded carbon is hard, but a lot of the emissions goes into manufacturing, rather than using, especially for smartphones.

- We can impact it by: using devices longer time; we (software engineers) should work on implementing leaner software; (governments should) regulate right to repair.

If you found this article useful, don't hesitate to share it. If you got it via e-mail, feel free to forward it to a person that will find this helpful.

To share your thoughts and opinions about the article - comment down below.

See you in the next article! 🤞